“Larry and Jim Fortado: Fishermen,” written by Robbie Bergerson, appeared in the book (1977) Transitions: Montara to Pescadero, An Oral History. inspired and edited by Canada College teacher Aida Hinjosa.

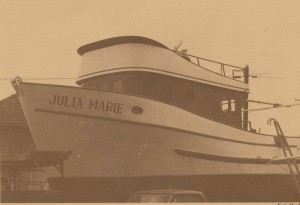

Photograph of Larry and Jim Fortado’s boat, the Julia Marie by Katie Murdock.

The blustering winds whipped around the point at Princeton and left the bay within the breakwater frothy with whitecaps. I arrived at the Princeton boatyard mid-afternoon in search of the nearly completely fishing boat of Larry Fortado. It wasn’t hard to locate. Amid the rusted skeletons and half-constructed hulls, there she sat, gleaming white and blue. It was solid and bigger than I had expected. As I mounted the wobbling stairs beside the boat, I was amazed by its actual size.

I descended into the engine room through a hole in the deck where work was being done on the interior of the boat. It was dark and the thick heavy smell of paint made things close, contrasting with the bright and windy atmosphere above. I teetered precariously on two girders and tried to stay out of the way as people milled about with paint brushes and buckets. Larry Fortado, dark and rugged, swept by, shouting instructions and moving things here and there. The frame of the boat had been built for Larry in 1975, and the rest is being completed by him and the other workers.

Larry was reared on a ranch, but for the last seven years, he has been a commerical fisherman. He started fishing with his brother, Jim, and for the past year, the two have fished the waters between Alaska and Mexico on Jim’s new boat. The fish, they say, follow currents and so, in the natural sense, a fisherman, too, follows the currents of the sea. However, fishing has become quite scientific. Larry showed me the spot in the engine room where meters will record the passage of bait beneath the boat. With a grin, he says: “A good fisherman still watches the birds diving into a run of anchovies.”

Listening to Larry talk about fishing one can feel his close tie with the ocean. He speaks of experiences good and bad, of throwing line after line in and filling the hold with salmon. The fish are “gutted” and laid out on the ice to preserve freshness. But fishing is not an occupation without hazards. Recalling a bad storm, with 40-mile-an-hour winds, Larry tells of his exhaustion as the boat finally pulled from safe waters. The crew dropped anchor right inside the breakwater and men fell asleep, leaving the boat to be berthed until morning.

Our conversation continued and while we talked, Larry instructed his wife Mary, “Ya got anymore paint left? Let’s get that lazarette over there on that wire.”

Amidst the hollow banging and clatter, Jim Fortado, looking very much like his brother, appeared. Friendly, with a wide grin, he seemed eager to talk of fishing.

“Ya gotta have some kind of regulations. Like the crab–ya can’t take on feamles–have to be 6 1/2 inches or ya throw ’em all back. So, ya know, you’re bound. In the old days, there was no regulations. Ya know, they just wanted to profit,” he said of the old fishermen. “They never thought of the future. They just didn’t see it. You know fifty or sixty years ago in this country they didn’t think anything was gonna happen. There’d be trees forever; ther’d be coal forever; there’d be fish forever. But now everybody realizes there isn’t. So you have to have regulations. Of course, we don’t like a lot of regulations,” he said with a grin.

“Things like limited entry. We’re gonna get that within the next coupla years. That’s like what Alaska has. You have to buy somebody else’s license. In other words, there’ll be maybe a thousand licenses and if somebody wants to get in they’ll have to buy an existing license from someone. Right now, a commercial fishing license costs only $35 per boat and $35 per man, but like in Alaska, if ya want to fish up there, I hear a permit costs ya $10,000. It’s like a liquor license.”

Now the two brothers, facing one another, balancing on girders, were really getting warmed up. All kinds of fishing talk started to flow. They told of the small group of commercial fisherman around Princeton. The eight or ten are a tightly knit bunch, close, yet competitive.

Competition with foreign fishermen does not concern the Fortado brothers.

“Foreign fishermen can’t fish salmon anymore, or crabs, or Black Cod or Rock Cod,” said Jim.

“Last year was our best year for crab; this year is our worst one.” And so it goes with fishing or farming or any occupation that depends on the cycle of nature. Jim predicted that the drought and man’s pollution would begin to affect the fishing in about three years.

The fishermen of Princeton consider the Coast Guard to be a good friend.

“They just inspect you sometmes,” said Jim. “Like once this year, they stopped a buncha boats and inspected ’em for fire extinguishers, and it’s a good idea. It’s just a pain-in-the-neck but they very seldom stop you.”

Federal Agents also check the fishing boats occasionally.

“They have a ‘Hot List,’ kinda,” Jim recalled, “and they think a lot of boats are bringing in marijuana and stuff. I found out later my boat was on the list. They never did contact me for some reason.” Teasingly he continued, “That was when I had a mustache, so I really looked like a mafioso, ya know. They couldn’t figure out how a little country boy like me could have a $100,000 boat unless I was runnin’ marijuana.” They all laughed.

“Naw, they never really hassle us,” he admitted.

Princeton Harbor is a Harbor of Refuge where any vessel can put in, in time of trouble, without penalty. The harbor will always remain a Harbor of Refuge because it was built by the Federal Government with Army Corps of Engineers’ money.

Jim estimated that about thirty acres will be used to construct the new marina which is being planned at Princeton.

“The fishermen are definitely in favor of the new marina. I don’t know if you saw all these boats around here,” he said of all the rusty remains in the boatyard. “About ninety percent of those boats were anchored out there and sunk in one of the storms of the last three or four years. It’s a Harbor of Refuge, but I wouldn’t call it very safe anchorage. It’s only safer tha n outside when it’s a south wind. One year we had thirteen boats up on the beach. My brother and I hauled most of ’em out.

“When we get a new marina in, they’re gonna put another little breakwater around which’ll stop all the wave action, and will have slips to tie up to.”

To emphasize the point, Jim told of a couple of drownings.

“There was a guy drowned here this winter. He was tryin’ to get his boat in a storm and he fell off the boat and drowned. Two years ago, another kid drowned. If we had a marina, ya know, it wouldn’t have happened.”

Considering the price of salmon in our local fish markets, it would seem that commerical fishing would be a prosperous business. Not so, the Fortado brothers claimed.

“Why then did you get started in this line of work?” I asked.

“How can you help it, being our here on the coast, near the ocean,” Larry stated simply.

Then, as if remembering a mutual joke, the two brothers replied in unison: “It seemed a good idea at the time,” and our laughter reverberated within the hollow hold.

Story by Robbie Bergerson